Kew’s exhibition, “Joseph Dalton Hooker: Botanical Trailblazer,” highlights handsome illustrations and provides a personal and professional cross-section of the making of a Victorian scientific career. But tantalizing morsels hint at tensions between public needs and professional goals in the life of a scientist and in the operations of a scientific institution like Kew, leaving the visitor wanting more.

“Kew is what my father and I have made it by our sole unaided efforts,” claimed Joseph Dalton Hooker in the early 1870s, affronted by a Board of Works proposal to eviscerate the scientific function of Kew Gardens. The proposal to transfer Kew’s herbarium collections of dried plants to a new museum soon to be opened in South Kensington (now known as the Natural History Museum) was politically framed as an attempt to streamline government-funded institutions and reduce spending. But Hooker saw it instead as a direct attack on his scientific career.

He had strived for decades to support himself through botanical work, making expeditions to the ends of the earth to collect new species of plants for Kew Gardens. Finally, in 1855, his father, Sir William Jackson Hooker, the first director of Kew, was able to hire him as assistant director. And in 1865, with his father’s death, J.D. Hooker became director himself. But now, just when he had ascended to the rank that would allow him to shape botany into a properly scientific pursuit, this proposal threatened to turn Kew into a mere pleasure garden, and to turn Hooker himself into a mere public servant.

Of course, ever since Kew was made public in 1841, its director was expected to act, to some extent, as a public servant, assisting horticulturalist and farmers at home and abroad with various botanical conundrums. Hooker himself became known for his aid in transplanting useful plants to colonial outposts: bringing quinine and rubber from South America to India, and disease-resistant coffee from West Africa to Sri Lanka. But Hooker believed just as strongly that Kew must serve the needs of botanical science, and to that end the herbarium was essential.

Fortunately, the safety of Kew’s herbarium was secured by 1874, thanks especially to the exertions of that infamous firebrand evolutionist Thomas H. Huxley. But questions about the Gardens’ function remained. In fact, while this exhibit largely glosses over the near-catastrophe of the early 1870s, comical illustration from later in the decade arrest the visitor’s attention, depicting Kew Gardens as a place where the enjoyment of the public and the work of scientists directly conflicted. In 1883, the Gardens began opening at noon; but prior to this shift, an opening time of 1pm prolonged the morning hours that scientists and students could work in Kew, undisturbed by the baser concerns of the general public. This one extra hour of public access was the hard-won product of at least seven years of public protest, if we are to judge by the date on a large cartoon: Inside the Gardens’ walls the privileged few luxuriate while the rabble pickets outside with signs like “Down with the select arrangement. No peace until satisfied” and “Give the public justice.” This cartoon, as with other such images in the exhibit, is inexplicably unreferenced, which is a shame, since visitors could better understand the illustrations’ significance with knowledge of their sources.

But Hooker’s place as the gatekeeper of Kew’s scientific reputation was also hard-won and it’s easy to understand his staunch defense of the Gardens as, first and foremost, a place for science. Both his and his father’s early careers had not been easy, and in building the scientific reputation of Kew, he built himself into a scientist in parallel. His trips around the world had fed the growing herbarium; according to the exhibit, over his 70-year career, Hooker identified more than 12,000 new plant species. Hooker sketched many of his collections while he was in the field. It’s wonderful to see the handwritten evidence of fieldwork found in researchers’ field notebooks, and Hooker’s sketches of plants and landscapes are some of the most engaging illustrations in the exhibit, drawing the visitor in to Hooker’s travels.

Using these collections, Hooker also asked larger questions about plants. In 1839, when he was only 22, he set off on his first long voyage, working as the assistant surgeon on an Antarctic expedition (though he preferred, according to the exhibit, his unofficial title of ‘Botanist to the Expedition’). Observing patterns of similarity and difference between plants found on the continents he visited gave him a lifelong fascination with the geographical distribution of plant species.

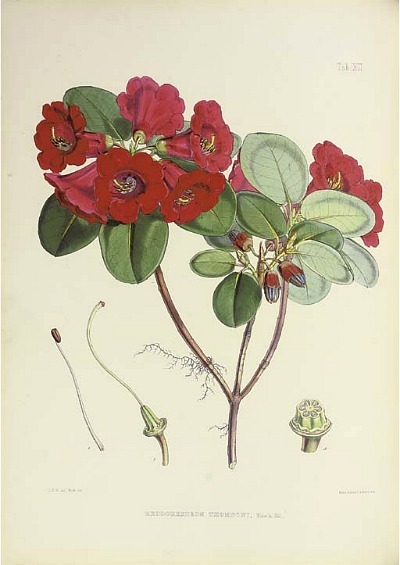

In highlighting Hooker’s astute observations of the geographical distribution of plants, the exhibit also presents a rather funny incongruity. Hooker is credited in one breath with cultivating non-native plants like quinine and coffee in the colonial landscape, and in the next with a prescient understanding of the ecological dangers of non-native species. In particular, we are told that upon visiting various islands in his travels around the Antarctic, Hooker became aware that non-native species were damaging to their “unique plant communities. These problems continue today with invasive non-native plant species overwhelming natural habitats, pushing some native species to the brink of extinction.” The irony of this is only heightened by Hooker’s renown for bringing the seeds of unfamiliar varieties of rhododendron back from the Himalayas. As popular plants in the Gardens, some of these may still be seen today in Kew’s Rhododendron Dell—as well as outside the garden where some “escapees” have come to act “invasively,” and are considered a non-native nuisance.

This apparent contradiction is no mistake—in fact, it reflects a cognitive dissonance that still thrives in biology, where organisms may sometimes be cast as emigrants and other times as invaders, where one moment one is a great success in a new ecological niche and the next a weedy marauder. The identity that a newly introduced species assumes rests to a large extent on cultural context rather than biological fact—which supports no opinion either way.

To be fair, though, J.D. Hooker’s scientific legacy is felt more in evolutionary biology than in invasion ecology. Hooker began his 40-year friendship with Charles Darwin just as he was setting off on his Antarctic expedition in 1839. And by the time Hooker left for the Himalayas in 1847, Darwin had confided in him his developing theory of natural selection. Thus, on this adventure, Hooker travelled, as a video in the exhibit says, with “a shopping list for Charles Darwin,” acting as Darwin’s eyes and ears in the field. “I congratulate myself in a most unfair advantage of you,” Darwin wrote to Hooker, “viz in having extracted more fact and views from you than any other person.” Considering what it must have meant for Hooker to have the seed of Darwin’s theory already planted in his mind a dozen years before the publication of On the Origin of Species, for him to see the vegetation of the Himalayas through that lens, it’s easy to understand how Hooker’s assistance and—later—his support of natural selection became indispensable to Darwin.

“Joseph Dalton Hooker: Botanical Trailblazer” does a good job of touching on many of the major themes in Hooker’s life and work and it is a worth a visit. But you must hurry to the Shirley Sherwood Gallery of Botanical Art, for the exhibit closes on Monday 9th April.

For Further Information:

The exhibit has a very nice little companion volume, which can be purchased at the Kew gift shop, and features a great introduction by historian of science Jim Endersby. I admit that I have not read his book Imperial nature: Joseph Hooker and the practices of Victorian science, but it looks like within its pages you can find out more about the near-demise of the Kew Herbarium in the early 1870s, a controversy that was named the “Ayrton Affair” after the head of the Board of Works, Acton Smee Ayrton. (The Ayrton Affair was also just one element within the Royal Commission on Scientific Instruction, also known as the Devonshire Commission.)

For more on the history of the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, check out their cool historical timeline.

If you would like to learn more about why I put “invasive species” in scare quotes, read out my own article on the subject at The Naked Scientists and check out this 2011 Nature article, entitled “Don’t judge species on their origins,” which you can actually read for free here, thanks to the US Forest Service!

Hi Rachel,

I reviewed Endersby’s book in 2009, if you’re interested:

http://thedispersalofdarwin.wordpress.com/2009/03/15/book-review-jim-endersbys-imperial-nature/

Thanks, Michael, I will check it out. You know, I am more into contemporary science, but of course you can’t be a historian of biology without some interest in and knowledge of the Victorian era!